What is aphasia?

You’ve been diagnosed with aphasia. Find out more about what it is, and what you can do.

You know what you want to say, but the words just won't come. You look at the newspaper, but you just can't take it in. You struggle to write a sentence or even a single word. You find it hard to follow conversation or verbal instructions.

These are all symptoms of aphasia. Aphasia happens when there’s been damage to any of the parts of the brain involved in language, often as a result of a stroke or a brain injury. And it can happen at any age.

Aphasia doesn’t directly affect the muscles of speech or writing themselves; it affects the ability of the brain to process the language that underlies speech and writing.

The impact of aphasia on the person affected and on their family and friends can be huge. It’s not just the everyday practicalities that become challenging; it’s the whole process of connecting with people, sharing thoughts and feelings. It can affect your confidence and your sense of who you are as a person.

Does aphasia vary from one person to another?

Yes, there are many different types of aphasia, because different parts of the brain deal with different aspects of language, so the difficulties will vary according to the site and extent of the damage. The effects can vary from mild to severe.

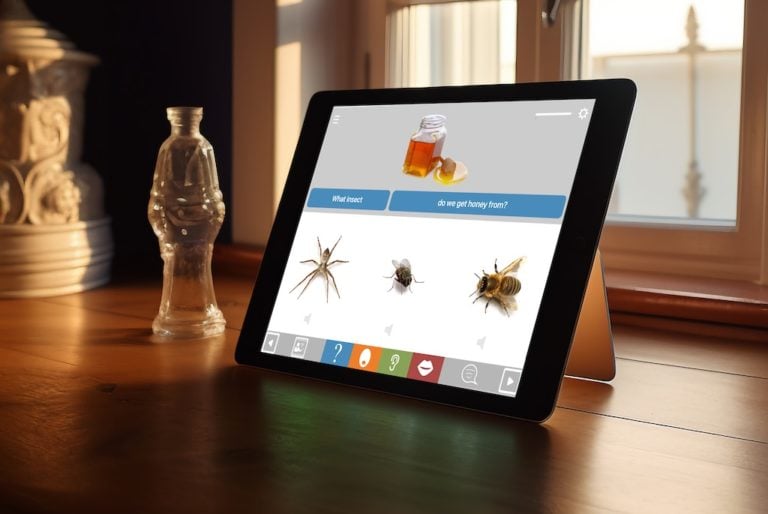

For this reason it’s important that therapy be geared towards the individual’s needs. If you’re lucky enough to have a speech-language professional supporting you, you can get guidance with this. But many people are able to access little or no help with their aphasia, especially in the long term.

Will it get better?

People tend to improve over time, and this improvement can continue for many years. Although medical professionals are sometimes known to suggest that improvement tails off after 6 months or so, most people’s experiences are that improvement continues for much longer than that. However it is rare for aphasia to resolve completely, and typically people have to learn to live with some degree of difficulty.

Can therapy help?

Some people can improve a lot with therapy. Others improve less. It can be hard to predict who will improve and who won’t. Research is ongoing to try and understand this better (PLORAS study: Predicting Language Outcome & Recovery After Stroke). What is known is that the people who do best:

– have more intensive therapy, and for longer

– have therapy that is personlaised to their own needs

– carry out therapy at home as well as with a therapist

(source: RELEASE study, Brady et al 2022)

What can other people do to help?

Allow plenty of time. Don’t rush things. Aphasia is less problematic if the person is relaxed.

Don’t change topics quickly without warning.

Slow down – but not so much that it feels unnatural. It’s better to slow things down by pausing to allow time to process what you just said, rather than by over-slowing your rate of speech.

If you’re discussing something important, or if there are choices to be made, it can help to write down key words on a piece of paper during the course of the conversation The person with aphasia can then use these to refer back to something that was said earlier, without having to say the words.

For some people it’s easier if you ask questions that have a yes or no answer. But bear in mind that with aphasia yes/no responses can get muddled, so be sure to double check if it’s something important.

If the person has difficulty understanding, support what you say with helpful gestures, e.g. if offering a drink, gesture drinking.

If possible, reduce background noice and distractions, e.g. by turning off the TV

Don’t pretend you’ve understood if you haven’t. If something remains difficult to understand, acknowledge that and suggest coming back to it later.

Meet other people with aphasia

Aphasia is more common than you might think – approximately one in every 270 people has aphasia. Depending on where you live, you might find there’s a group locally where you can meet other people with aphasia for mutual support. If there’s nothing locally, you can meet people online through national support networks.